Wartime Diplomacy. Part IV.

07.08.2020

Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the End of World War II we would like to present another series of articles about the role of Polish diplomacy during that period: 15. Treaty that saved thousands of Polish lives, 16. Embassy on inhuman land, 17. From Africa all the way to New Zealand, 18. Jan Karski’s report & 19. The Paraguayan passports.

Wartime Diplomacy. Part IV.

15. Treaty that saved thousands of Polish lives

30 July 1941 saw the signing of a treaty between Poland and the USSR which became a major point of contention in Polish political life, causing a serious governing crisis but, at the same time, allowing for the release of thousands of Polish citizens whom the Soviets had deported deep into the USSR after 1939.

The talks between Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and the Soviet Ambassador to London Ivan Mayski (whose names as signatories gave the treaty its name) began shortly after the USSR was attacked by Nazi Germany and joined the anti-Nazi coalition. The Polish Prime Minister, encouraged by the British authorities, decided on taking part in negotiations with the Soviets which eventually led to the normalization of Polish-Soviet relations. The Sikorski-Mayski agreement reinstated Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations, revoked Soviet-German treaties from August and September 1939, and provided for the formation of the Polish Army in the Soviet Union and the release of Poles held captive in Soviet prisons and exiled into the USSR. Prime Minister Sikorski is remembered to have stated: “No more can be achieved in this matter. Whoever favours refusal fails to see the reality.”

Critics of General Sikorski complained that the treaty had failed to secure Soviet recognition of the pre-war Polish-Soviet border, set out in the 1921 Treaty of Riga. They also protested the use of the term “amnesty” with regards to Polish citizens released from Soviet captivity as suggesting criminal connotations. They also criticized the fact that the leadership of the Foreign Ministry was excluded from the negotiations and accused Prime Minister Sikorski of violating constitutional competences of the head of state. President Władysław Raczkiewicz refused to sign the treaty and its text was not published in the Official Journal of Laws. Foreign Minister August Zaleski tendered his resignation, as did Justice Minister Marian Seyda and Chancellery Minister Kazimierz Sosnkowski. Yet, all things considered, the argument in favor of signing the treaty turned out irrefutable: the agreement saved the lives of at least 115,000 Polish citizens who were released from Soviet captivity. They reached assembly points where Polish Army was formed and soon left the Soviet Union.

Caption:

Polish text of the Sikorski-Mayski agreement of 30 July 1941, signed by Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski

16. Embassy on inhuman land

The main task of the Embassy of the Republic of Poland opened in Moscow after the conclusion of the Sikorski-Mayski agreement was to provide assistance to deported Polish citizens in the USSR and, inseparably connected with it, to support the recruitment campaign for the Polish Army in the USSR. The Polish mission, like the diplomatic representations of other countries in Moscow, was moved to Kuibyshev, which was further away from the European war theatre, at the beginning of November. In the following weeks, a network of Polish embassy delegations was established in the USSR. They did not formally have the status of consulates, but in fact performed most of the tasks of a consular nature: they registered Polish citizens and issued them with identity documents, tried to provide work and minimum health and social care conditions, organized education and cultural life, and directed arrivals to centers forming military units in Buzułuk and Tashkent. Persons of trust who were recruited from the people sent to the USSR helped the delegations; many of them were later arrested by the Russians. In total, from August 1941 to April 1943, the Embassy and its delegations provided assistance to almost 270,000 people from 57 regions and 704 districts of the Soviet Union.

The Polish Army formed in the USSR reached in October 1941 more than 40,000 people in numbers. People joining the army were accompanied by civilians released from labor camps and exiles. So many people lacked clothing, medicine, food, weapons and wax equipment. In view of the dramatic supply situation, the army commander, General Władysław Anders, agreed with Stalin to evacuate the Polish Army to Iran, where the forming troop units could count on better conditions. The decision to leave the USSR by the Polish Army and a group of several thousand civilians greatly expanded the scope of activities of the Polish mission in Tehran. The scale of the mission's tasks is evidenced by the number of people evacuated: in 1942, nearly 116,000 people from the USSR came to Iran, including more than 78,000 military personnel and more than 37,000 civilians.

Caption below the illustration (two photos):

A passport issued by the Delegation of the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Samarkand. On the reverse – a list of articles – clothes and food – issued to a Polish citizen by the person of trust (M.Z.) from the Embassy.

17. From Africa all the way to New Zealand

Large groups of civilians, including women, children and men unfit for military service, were evacuated from Iran to multiple locations across the world: to British East Africa (camps in Tanganyika, Uganda and Kenya – altogether 20,000 people) and to New Zealand (Pahiatua camp, approximately 800 children).

Dramatic fate awaited Polish citizens evacuated from the Soviet Union to India. The Polish Consulate General in Bombay provided assistance for approximately 600 Polish orphans who lived in poor conditions by recruitment centers for the Polish Army. The operation to transport the orphans through Iran and Afghanistan to India was organized by the Polish Consulate and supported by the Polish Red Cross. The children were placed in care centers in Balachadi, made available thanks to the generosity of Maharaja Jam Sahib.

Also other non-European diplomatic missions, whose countries were not directly involved in the war effort, helped Polish citizens obtain identity documents and visas.

Assistance to those in need also came from legations and consulates in Latin American countries. Alter Polish citizens were evacuated from Iran, approximately 1,500 refugees found their way to Mexico. They were placed in a Santa Rosa camp near Leon and protected by the Polish Legation in Mexico. Edward Raczyński, who replaced August Zaleski as Foreign Minister, wrote in a circular to Polish foreign missions on 28 April 1943: "The catastrophe of war has thrust large numbers of our citizens all across the lands free from enemy occupation and has placed upon us the duty to protect them on a scale larger than any pre-war effort."

Caption:

A declaration for a participant in the transport from Iran to British East Africa

18. Jan Karski’s report

A unique chapter in the history of Polish diplomacy was written by those who provided various forms of assistance to Polish Jews during the Second World War. Few of them were able to leave Poland as part of the September 1939 emigration wave. In occupied by the Third Reich Poland, Jews were deprived of all civil liberties, forced into ghettos, severely punished for breaking the regime's discriminatory laws and left to die. From 1941, Jews were subjected to systematic extermination. In 1942, the extermination of Jews became part of a wider Nazi German plan of total annihilation of all European Jewish population. By 1945, approximately 3 million Polish Jews lost their lives in the Nazi German extermination camps and ghettos. Between 1939 and 1941, from 100 000 to 300 000 Polish Jews were deported from the Soviet-annexed Poland deep into the USSR along with other Polish citizens.

Jan Karski played a special part in the history of Jews in occupied Poland. Karski started his diplomatic career before 1939 as an intern at the Consulate General of Poland in London under his family name of Jan Kozielewski. Karski went on to pursue his diplomatic career at the headquarters of the Polish foreign service. He worked for the Home Army’s information service and he was engaged in clandestine activities. He travelled as a courier between Poland, France and Britain. In 1942, Karski brought the first extensive eye-witness reports about the Holocaust to the Polish government-in-exile and to the leaders of the free world. In July 1943, Karski presented his report to the U.S. President F. D. Roosevelt. In his conversation with Roosevelt, Karski said: ”If the Germans do not change their methods towards the Jewish population, if there is no Allied intervention – either by repression or any other way - or if no unforeseen circumstances arise, the Jewish population of Poland, with the exception of members of the Jewish resistance, will cease to exist.” Jan Karski’s reports formed basis of the diplomatic note sent by the Polish government to governments of 26 countries, signatories of the United Nations Declaration, on 10 December 1942. Later on, the note was published as “The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland” and distributed by the Polish Foreign Ministry.

Caption:

Diplomatic passport issued for Jan Karski before his mission to the United States of America in 1943

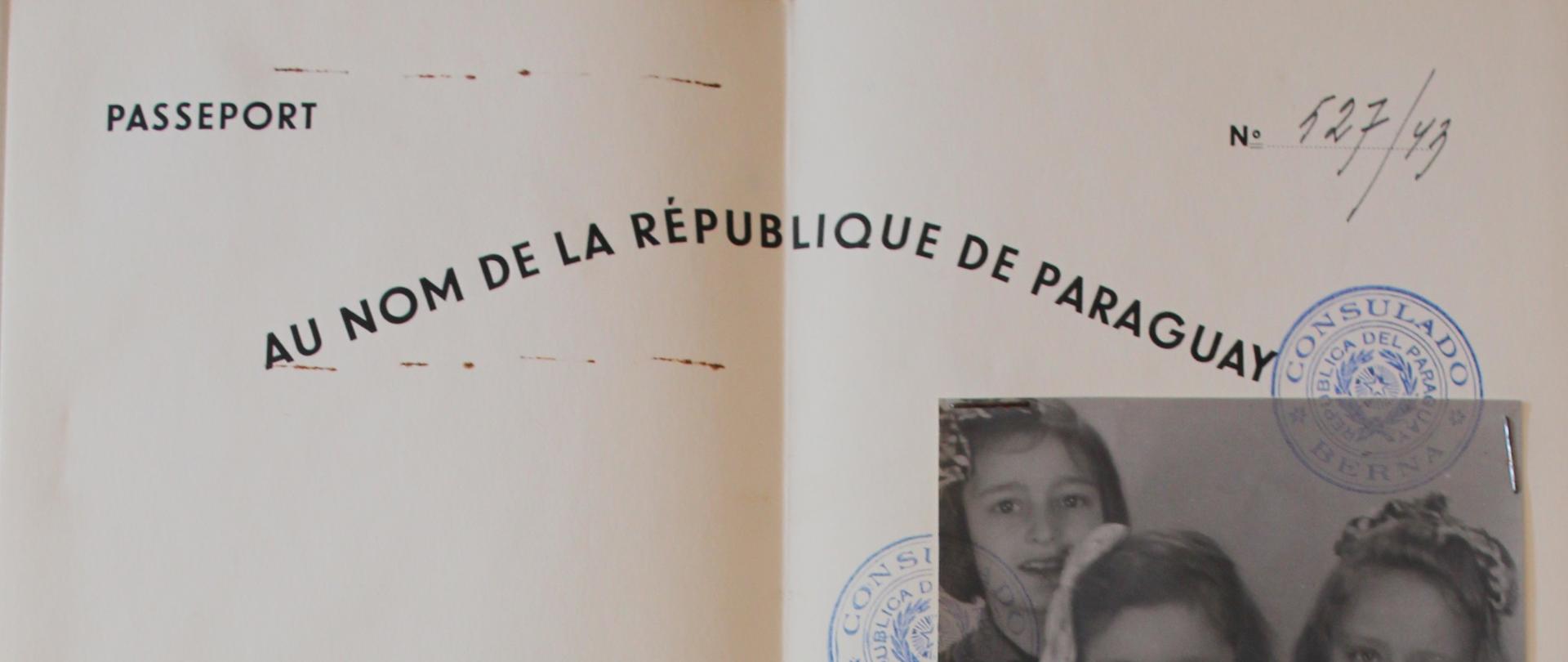

19. The Paraguayan passports

Since the outbreak of the Second World War, and especially in 1942 and 1943, illegal assistance was provided by the Polish Embassy in Bern, Switzerland for Jewish citizens of Poland, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Hungary and Jews deprived of German citizenship. Polish diplomats: Konstanty Rokicki, Stefan Ryniewicz and Juliusz Kühl organized, with full knowledge and agreement of the Head of Mission Aleksander Ładoś, production of illegal Paraguayan passports (and, in rare cases, other South American passports). First, original blank passports were bought from South American honorary consuls in Bern and then they were issued to Jews to protect them against deportation to extermination camps and to give them a chance to survive in an internment camp for foreigners. The Polish Embassy in Bern issued at least 1,000 such passports. Each passport was issued for several family members. The passports reached only some Jews. They saved at least 800 lives.

The Head of Mission in Bern Aleksander Ładoś sent reports to the Polish Foreign Service Headquarter with information about the illegal passport production: “Our operation consists of obtaining South American passports from friendly consuls, especially from Paraguay and Honduras. The passports are kept here while their copies are sent to Poland. This keeps people safe because as “foreigners” they are placed in relatively decent conditions, in special camps. They would remain there until the war is over and we would maintain correspondence to stay in contact. Then, we issue written statements to consuls confirming that the passports were used to save people’s lives and they shall not be used otherwise”.

Caption:

A Paraguayan passport issued by Vice-Consul Konstanty Rokicki

Edited by: Ambassador Marek Pernal

Materials

15_Polish text of the Sikorski-Mayski agreement of 30 July 1941, signed by Prime Minister Władysław SikorskiFot15.jpg 5.21MB 16a_A passport issued by the Delegation of the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Samarkand.

Fot16a.jpg 2.36MB 16b_A list of articles – clothes and food – issued to a Polish citizen by the person of trust (M.Z.) from the Embassy.

Fot16b.png 1.41MB 17_A declaration for a participant in the transport from Iran to British East Africa

Fot17.tif 22.56MB 18_Diplomatic passport issued for Jan Karski before his mission to the United States of America in 1943

Fot18.jpg 1.60MB 19_A Paraguayan passport issued by Vice-Consul Konstanty Rokicki

Fot19.JPG 3.71MB